Appendix to the Second Edition of "Popologetics" (if ever there is one)

In publishing a book, I made a rather unpleasant discovery: my book wasn’t perfect. Comments that students or reviewers have made have shown me this. Pity. I thought it was perfect when I published it. Granted, some of the comments were unfair, or the product of inattention to what I actually said in the book. But some were valid, or at least showed a genuine need for clarification on my part. In any case, I thought that this is as good an occasion as any to answer some of those comments, and in part to rectify the book’s flaws. So here, in no particular order, I shall attempt to do just that.

1. It is only by the power of the Holy Spirit that any apologetic is effective.

One of my students at WEST pointed this out in saying, “It may be too obvious to say, but this stuff only works because the Spirit empowers it, right?” Well, half right. It does only work because of the Spirit’s enlightening power, but it is by no means too obvious to state it up front. I was a bit abashed, to be honest. I was so focused on method, on theory, and so forth, that I neglected addressing the role of God in this whole process. There’s not so much to say about it except this: nothing about popologetics works without the Spirit’s empowering, guiding influence. We are absolutely dependent upon him in our apologetical encounters. Here’s where method ends and reliance upon the sovereign God of mercy begins. And if that is true, then the only way to express that dependence is prayer, prayer, and more prayer. Every conversation, every movie night, every engagement with the unbelief woven into popular cultural imaginative worlds, must be bathed with prayer; prayer for discernment, for an honest appraisal of our own hearts, for a reflection of Christ’s love in our conversation with others. Not to mention that was a big mistake. One does not simply assume the Holy Spirit (just as one does not simply walk into Mordor).

2. I used misleading language in “step 4.” It is actually about is finding idolatry, the deceptive distortion of common grace.

My wife pointed this out to me when she substituted for my apologetics class for high school seniors at the Christian International School of Prague. She noticed that the way I phrased step 4 led to a misunderstanding in the students. They focused on the sinful, evil perverse behaviors (violence, sexual promiscuity, etc.) that they saw in a piece of popular culture (akin to the “Ew-Yuck” response that we discussed in chapter 6). That was a mistake on my part. I used those words because idolatry is an evil perversion of the common grace that God gives us. But that deceptive distortion can sometimes look very attractive (A.K.A. "Angel of Light Syndrome," see 2 Cor. 11:14). So step 4 is really about finding the false religion, the false salvation offered by the idol or idol system of this particular popular cultural imaginative world.

Parenthetically, I ought to point out an error I notice frequently when students go a-hunting for idols in popular culture, especially movies: your target is not the idol of this or that character, but the idol of this imaginative world as a whole. You need to seek a wide perspective on the idolatry offered by this popular cultural work. So, for instance, if you have a drug addict in a movie, chances are that drugs function as an idol for him. But unless there are specific clues in the world of the film that the filmmaker shares that drug-praising perspective, then chances are it is not an idol of the imaginative world of the film itself.

In my method, for some reason, step 4 seems particularly prone to misinterpretation: look for the controlling idol or idols (and not just deviant behaviors) of the imaginative world itself (and not just of this or that character).

3. Our posture toward the world should be like that of Jesus, not like that of the “Bruised and Bleeding Pharisee.”

One criticism I've heard repeatedly from Evangelicals is that the whole thesis of the book is flawed, that Christians have no business dealing with something as sinful as popular culture. One woman wrote to me: "There is no biblical justification for studying popular culture!" This woman is no dolt – she is theologically savvy. But she believes that getting too involved in popular culture compromises our Christian walk. I thought I dealt with that in chapter 6, but I guess I should have spent a bit more time on it. So here's why I think those people are dead wrong.

In the Babylonian Talumud (Sotah 22b), there is a passage that mentions 7 types of Pharisees. Only type 6 and 7 are held up as worthy, and the rest are derided as types of hypocrisy. The third type is the "bruised" or "bleeding" Pharisee, one who so feared temptation to lust that they would put on blindfolds when they went out so that they wouldn't even have to look at a woman. Consequently, they ran into stone walls and became bruised and bleeding. Scottish Bible scholar William Barclay mentioned these varieties of Pharisee in his commentary on Matthew (The Daily Study Bible: The Gospel of Matthew, vol. 2, 1957, p. 330). And through Barclay's commentary, it was assumed that there was an actual group of Pharisees who were devoted to this type of piety, and many Evangelicals now talk about "The Bruised and Bleeding Pharisees." Given the actual passage in the Talmud, that is far from certain. But even if there was no such group, it is still a really good illustration of a certain type of Christian piety that cuts itself off from the world to ensure purity. This is a grave mistake. Though we may want to avoid parts of popular culture, our attitude towards popular culture as a whole should avoid pharisaical withdrawal.

When I look at Jesus' own approach to the surrounding culture, I see something altogether different. I see him hanging out with all the wrong people, the hookers and drug dealers of his day, company that shocked the religious types. I'm guessing that the prostitutes that Jesus was spending time with dressed in clothes that were provocative. But it didn't seem to bother him. Rather than fearing pollution from dirty people, like the Pharisees, Jesus' kind of holiness actually drew him to dirty people. Like the leper of Luke 5:12-15, Jesus wasn't the one in danger of contamination. Rather, it was the leper who got "contaminated" by the cleansing power flowing from Jesus. Jesus had nothing to fear from the unclean – quite the other way around. By hanging out with Jesus, dirty people became clean.

Now you could say, "Well, that was Jesus. He was special. He was stronger, immune from temptation, etc." And I'd respond: No, he wasn't. He was not above temptation, according to Hebrews 4:15, Jesus was tempted in the same ways we are, and yet was without sin. True, Jesus had a unique place as the God-man, the Messiah, and so he had a special anointing of the Spirit to reach out in ways that we cannot (like dying on the cross for the sins of his people). On the other hand, that power and ministry of reaching out to the dirty is not unique to Jesus. Jesus makes it pretty plain in John 14:12 that we are to follow the pattern of ministry that he created: "I tell you the truth, anyone who has faith in me will do what I have been doing. He will do even great things that these, because I am going to the Father." How is this possible? Because of the power of the Spirit. In John 11:37-39, Jesus invited people to come and drink the "living water," promising them that if someone believed in him, "streams of living water will flow from within him" (v. 38). John explains that this living water is nothing other than the Spirit, the same Spirit that empowered Jesus' ministry. The image that Jesus uses of the artesian well points to the sort of flowing out of healing influence that he had: dirty people get clean by hanging out with those through whom the Spirit of Christ flows. Jesus didn't fear contamination, but quite the contrary, his type of holiness drew him to the unclean. And so it is for us, if we want to follow Jesus' pattern of mission.

It is true that not all Christians should be engaging all types of popular culture. I tried to make that plain at the end of chapter 6. We should know where we struggle, what idols tempt us most. We are not to be fools. But the kind of "holiness" that draws us away from contact with the world is a bogus holiness. That is the gist of Arturo Azurdia's fine book, Connected Christianity: Engaging Culture without Compromise (Christian Focus, 2009). He argues from Jesus' High Priestly prayer in John 17 (especially 17:6-19) that the only type of valid Christianity is "worldly Christianity." By that provocative phrase he means a faith that is not of the world, but is definitely in it, engaged with it. That is our mission, and if we refuse it, we essentially refuse the sanctifying work of Jesus:

My prayer is not that you take them out of the world but that you protect them from the evil one. They are not of the world, even as I am not of it. Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth. As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world. For them I sanctify myself, that they too may be truly sanctified. (17: 15-19).

Sanctifying is not simply "becoming more moral" (though they are often connected in Scripture). Rather, sanctifying is about being set apart for mission. Jesus set himself apart for a mission into the world that culminated on the cross. We are likewise set apart for a mission into the world as a witness to his saving work. Refuse contact with the world, you refuse the mission, and the sanctifying that goes along with it. Or as Azurdia puts it:

'As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world' (v. 18). For this reason, a Christian disengaged from the world is a colossal contradiction – especially when this occurs in the name of piety. It is no mere disregard of the task assigned to us by Jesus. It is far worse. Disengagement seeks to invalidate the sanctifying benefits Jesus won for us at the cross. (p. 64, emphasis in original).

Not every type of Christian should be engaged with every kind of popular culture. But an overall strategy of cultural withdrawal, of a stubborn refusal to engage with popular culture per se, is a serious undermining of Christian piety.

"But," you may respond, "that's fine when it's people. But popular culture isn't actually people. Do we really need popular culture to connect with the world around us?" That leads me to my fourth point.

4. Engaging with popular culture is not optional if we want to connect with our world. That is to say, there is no substitute for engaging popular culture.

One comment I've heard a couple times is, "We already have sin in our hearts. We already see idolatry in the world around us. Do we have to go looking for it in popular culture? What's the point? Can't we just do without it?" And the answer is a resounding NO. Why not? Why can't we do without popular culture?

For one, popular culture is an art form, and that means that one of its functions is to clarify and crystallize cultural motifs and attitudes in a particularly illuminating way. When we are dealing with people, these motifs and attitudes may lie buried deep within, unrecognized. But in popular art, those motifs, attitudes, grace and idolatry all surface in an imaginatively rich way, one that confronts the viewer, listener or player with more force and clarity than could be had in any other way. If we truly want to know what has captured the popular imagination, nothing beats a powerful popular cultural work.

Some Christians cling to the notion that the structures of and responses to popular culture are somehow fake. They believe that "fictional" means "false," and so any heart-responses we have to popular culture are likewise false. This is absolutely mistaken. The imaginative worlds may be fictional, but the issues of human concern, and the heart-responses of the audience, are real. In a brilliantly written episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer in which Buffy's mother dies unexpectedly of a brain aneurysm, it is a real struggling with the pain, confusion and brutality of the death of a loved one, played out in a fictional setting. Just because there was no factual death (the actress who played Buffy's mother was just fine) does not mean that the grief observed vicariously by the audience is any less real. It engages their imaginations and emotions; they struggle with Buffy and her friends to make sense of it all. It brings it home in a crushingly clear way, and yet without having to actually having to lose a loved one in the real world. As someone who has lost a loved one, the episode absolutely rang true. And it called for engagement - for reflecting on the raw, remorseless force of death, so that we could grasp more fully the depth and significance of the hope we have past death.

Second, popular culture deals in the hypothetical, in the fictional. And that gives it the texture of a "safe-zone" when discussing issues of human significance with non-believers (or even believers). I have found this to be true many times during our movie nights. It is very threatening to talk to people directly about stuff going on in their lives, their attitudes, their idolatry. But watch it together with them in a movie, and talk about the stuff going on in this or that character's life, and it is safe. There's a distance that makes it OK to talk about. They even want to talk about it, because they do want to talk; just not in a way that would leave them feeling judged and vulnerable. Popular culture provides a way to talk about it, and gives them some cover. In this way, you build trust with people until you have earned the right to address those issues in a more direct way.

For those two reasons alone, I believe there is no substitute for popular culture.

5. I should have discussed Christian liberty (Ro. 14).

One reviewer chided me for not discussing Christian liberty (what we as Christians are free to or not to do). I think he was right. The place in Scripture that deals most directly with this issue is Romans 14:1-15:7. Paul addresses dietary restrictions (possibly in response the Roman practice of selling meat in the marketplace that was sacrificed to idols). Paul addresses two groups in the church: the weak (those whose consciences did not allow them to eat meat), and the strong (those whose consciences did allow them to eat meat). The principle he formulates with regard to meat-eating has obvious application to other sorts of consumption, including the consumption of popular culture.

The best summary of this passage I've heard came from my mentor, Bill Edgar, in an apologetics class long ago: "Avoid a dictatorship of the weak, and avoid the strong trampling the weak." That is, those with weak consciences ought to refrain from instituting their weakness as rules for all believers. "I can't watch R-rated movies, therefore NO Christian should be allowed to watch R-rated movies." AND those who have freedom in this area shouldn't be flouting their liberty and dragging Christians with weak consciences to R-rated movies. That only causes the weak brother or sister to stumble. However, Edgar added, the weak ought not to remain weak. The strong ought to gently instruct the weak in a way that won't violate the consciences of the weak (as Paul himself does in 14:14-18).

In all cases, we should not judge the other, and so undermine Christian unity. Instead, we should seek to build the other up. Judging others is out of place. Why? Because he is ultimately accountable to God alone: "Who are you to judge someone else's servant? To his own master he stands or falls. And he will stand, for the Lord is able to make him stand" (14:4-5). That is to say, these issues are ultimately between Jesus and the believer, and no one else. Therefore, community rules regarding what sort of popular culture we should be allowed to watch are out of line. Rather, we should, each of us, learn to discern our own hearts; where we are weak, and where we are strong. Rule-making is no substitute (or rather, is an illegitimate substitute) for the slow, painful process of Spirit-guided discernment regarding our own hearts (and the hearts of our children).

Still, when I teach on popologetics, I have Christians (often pastors) challenge me: "Surely there is some line that we can draw, some place where we can say 'Christians ought not watch this!'" And I reply, "Well, maybe, but I'm not the one to draw that line, and neither are you!" And I usually tell them the story about a friend of another mentor of mine. We used to meet for Bible study and prayer. And he told me about a friend of his whose mission field was strip clubs. This man would go into these places and talk to the girls, try to bring them the gospel, and try to get them out of that lifestyle. According to this guy's own testimony, the nudity and eroticism didn't bother him a bit. I would hasten to add that it is not my mission field. Knowing the weakness of my own heart, it would just feed idols and mess up my own walk with the Lord. I would dare say that 99.997% of men should not make it their mission field. But am I going to say to this guy, "No, no Christian male should ever do such a thing. You're way out of line!" No! Rather, I am going to praise God that he has gifted one of his own to withstand those challenges, who gave this guy freedom to be salt and light in a place of darkness and sleaze. I am going to thank this guy for his work and pray for him, because he is exactly where God wants him to be! Not my mission field, to be sure; but God bless him.

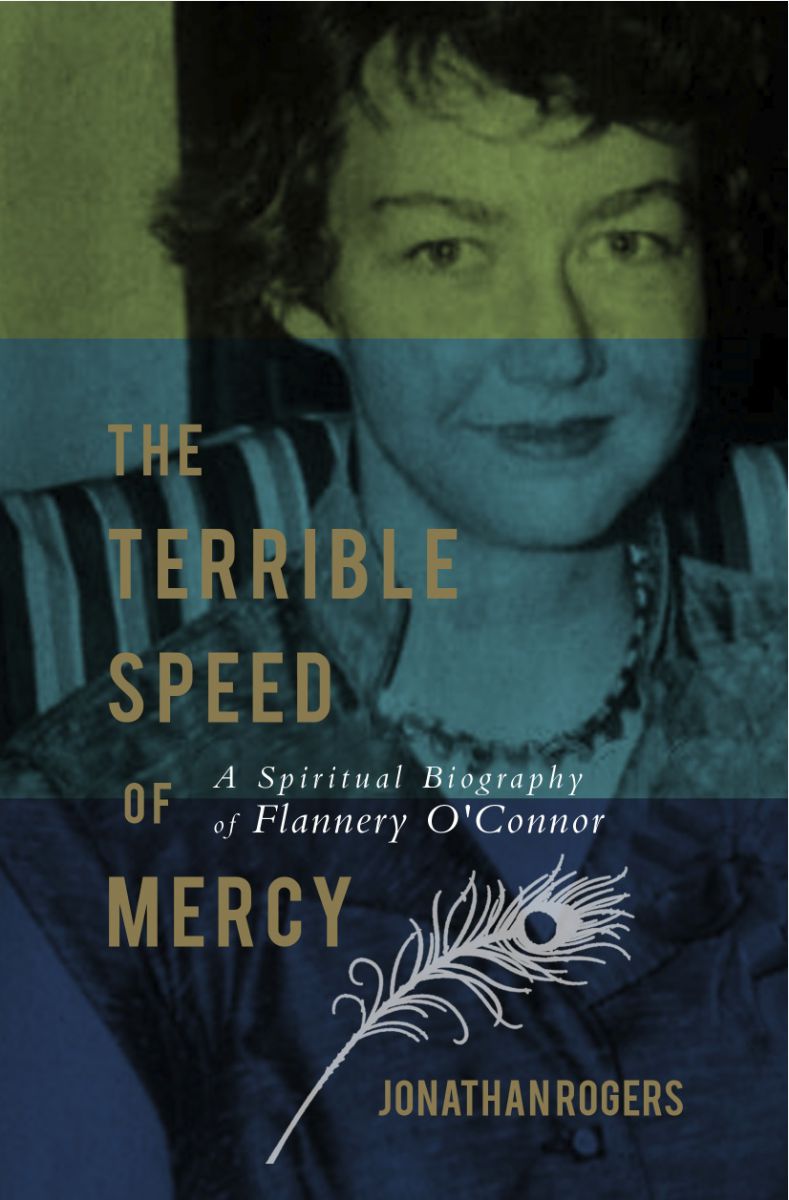

Let me give another, less Technicolor example: I have a Christian friend who cannot read Flannery O'Connor. I consider O'Connor to be one of the best (perhaps the best) American short story author of the 20th century. Her stories often involve seeing things in a deliberately grotesque, unsettling eye (because the fallen world is grotesque and unsettling). And they often involve disturbing violence. But violence in her stories often mark transcendence, a vertical insertion of God's terrifying grace into the human situation (such was the cross, if you think about it).  But that violence and grotesqueness was too much, too dark for my friend. She's fine with other Christians reading O'Connor. But by the same token, I would never in a million years drag this friend of mine to a reading of "The Displaced Person." The weak shouldn't legislate; the strong shouldn't violate.

But that violence and grotesqueness was too much, too dark for my friend. She's fine with other Christians reading O'Connor. But by the same token, I would never in a million years drag this friend of mine to a reading of "The Displaced Person." The weak shouldn't legislate; the strong shouldn't violate.

In the same way, in trying to engage our culture, getting to know the popular imagination, drawing lines and calling this or that out of bounds is just not healthy. It's meddlesome and undermines Christian unity. But don't violate the weaker brother or sister's conscience. Allow freedom to Christians to explore what his or her Lord allows him to explore.

6. Our engagement with popular culture ought to be more than utilitarian. It’s OK to enjoy popular culture gratefully.

One of my students asked a question that really hit home: "Isn't it OK to enjoy popular culture rather than simply trying to use it for evangelism or apologetics?" And he's absolutely right. I tried to bring this out in the book by saying that properly understanding popular culture leads into worship, but perhaps I should have said more. If we agree with the Westminster Shorter Catechism's assertion that our primary purpose is to "glorify God and enjoy him forever"; and if it is legitimate to enjoy God through his creation; then enjoying popular culture gratefully is simply part of being legitimately human. We can enjoy God through living in his world, rejoicing and enjoying what he's allowed to be all around us.

Arturo Azurdia makes this point in Connected Christianity. On page 72, he describes going to a baseball game and thoroughly enjoying it, absorbing the sights and sounds of the game he loves. He says, "I am exceedingly thankful for the privilege of being a live human being in this world," (his emphasis). Such a thankful enjoyment of human culture is part of a full-bodied Christianity. Rejection of such gifts is, in essence, a type of disembodied Christian spirituality that seeks refuge in a ghostly "spirituality." It is akin to docetism, a heresy that sought to "protect" Christ's divinity by saying that his human body was but shadow, an illusion (I mean, seriously, the Son of God suffering a bodily death and humiliation?!). But that is exactly what real Christianity affirms: that the Son of God came in the flesh (see 1 John 4:2-3). Real Christianity connects us to the world to which we've been sent. It's OK to enjoy it, as long as you see clearly the One who is glorified by it (versus putting your final hope in the gift itself, which leads to indulgence and idolatry).

One place where I'd take issue with Azurdia is with his examples of cultural experiences he is thankful for. He plays it rather too safe. They are all rather high-brow in a comfortable sort of way: the intermezzo from Cavalleria Rusticana, a P.D. James novel, Ansel Adams' photography, Kenneth Branagh's Hamlet, Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird, and Arturo Sandoval's jazz improvisations on trumpet (yeah, jazz has a rather strong following among social elites, despite its origins; from the barroom to the symphony hall). Heck, even his beloved game of baseball has a high-brow appeal; after all, Ken Burns made a documentary about it for PBS, didn't he? I would have much preferred him to challenge his readers a bit more to gratefully embrace popular cultural works. He could've said (and would've, were he me), "I am so thankful to God that I live in the world where Joss Whedon is  making blockbuster movies like The Avengers, which is fairly dripping with awesome sauce! Where DJ Earworm can take 25 Billboard hits and combine them into something that sounds better than any one of them alone! A world where a graphically rich game like Skyrim is possible, a place where I can slay a dragon . . . with my voice!" That, I submit, would cause a few Christians to sit up and take notice.

making blockbuster movies like The Avengers, which is fairly dripping with awesome sauce! Where DJ Earworm can take 25 Billboard hits and combine them into something that sounds better than any one of them alone! A world where a graphically rich game like Skyrim is possible, a place where I can slay a dragon . . . with my voice!" That, I submit, would cause a few Christians to sit up and take notice.

I wrote Popologetics both as a ministry tool and as a way to give Christians permission to enjoy popular culture. It's there, and a lot of it is awesome. So go enjoy it gratefully. Doing so will, by the way, better equip you for ministering to a dying world. But it's OK to enjoy it without having to consider ministry every second of every day. Be a full-bodied, worldly Christian (in the sense in which Azurdia used it – see above, point 3), and enjoy gratefully.

.jpg)

.JPG)

Comments

refreshing

Thanks, Kenny!

Sorry it's been a year since you posted this. I'm a bad bloglord. But I appreciate you're encouragement.

Peace,

Ted