The Problem with Pilgrimage

My family and I (sans my eldest, busy at university) returned recently from a trip to Israel. My wife teaches Old Testament at our local Christian school and has been bugging me to go for years. The opportunity to go in a way that was affordable finally came up (thanks to some friends who live in Tel Aviv), so off we went for a week, just before Easter. When we returned, friends and students have asked, "So, what was Israel like." And I always answer, "Beautiful and weird." It wasn't the most fulfilling spiritual experience of my life. It wasn't transcendent. It was beautiful and weird, and I don't mind saying that the hyperbolic language some Christians use to talk about the Holy Land bothers me deeply. Here's why.

Actually, before I tell you, I have a confession to make: We did not go to Israel the way most Christians do. We didn't go with a tour package, or as tourists staying at a hotel. We went and stayed in the apartment of some dear friends. These dear friends made all the difference, gave us insider knowledge, an informed perspective on our travels. Especially the guy, the dad of the family. His name is Stewart, and he's in the Air Force. He has been stationed for the past two years in Tel Aviv with some cultural exchange program the U.S. military has. You take a language exam, and if you score high enough, the military will ship you off to a destination like Israel or North Africa and tell you to study whatever. Basically, your job is to get to know the people there, and to let them get to know you, to prove to them that Americans are humans and aren't all jerks. So that is Stu's job, at least until his assignment is up. And he's been doing it beautifully. He's taking classes on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to get some perspective, and he's been talking to Israeli Jews at the gym, Israeli Arabs at the restaurant, etc. He had tons to tell us about the weirdness that is modern Israel. Any simplistic notion of Israel being God's country and Israeli Jews as being God's people simply won't do. It's a lot more complicated than that.

So let me talk about the "beautiful" part of it. Israel has some beautiful beaches. It has some surreally beautiful desert canyons. It has some wonderful food (the Arabs make the best food – shawarma and falafel to die for). Jerusalem's Old City is really cool, lots of ancient stone walkways. And you can find just about anything at the bazaars there. Although some of the people can be really rude, there are some really friendly people there too. And it's got an absolutely kick-ass music scene (Tel Aviv has got some incredible jazz musicians, and Israeli rap must be heard to be believed). So I am not anti-Israel in any sense of the word.

But I did and do have some problems with spiritual tourism, and the naïveté that too many Christians have when they go to Israel.

First, I was expecting to feel more in going to places where Jesus was. I was thinking that I'd experience some deep connection that I couldn't get elsewhere. I was wrong. I was wrong because those sites are now empty, built upon. Places like the Garden of Gethsemane, where you can see

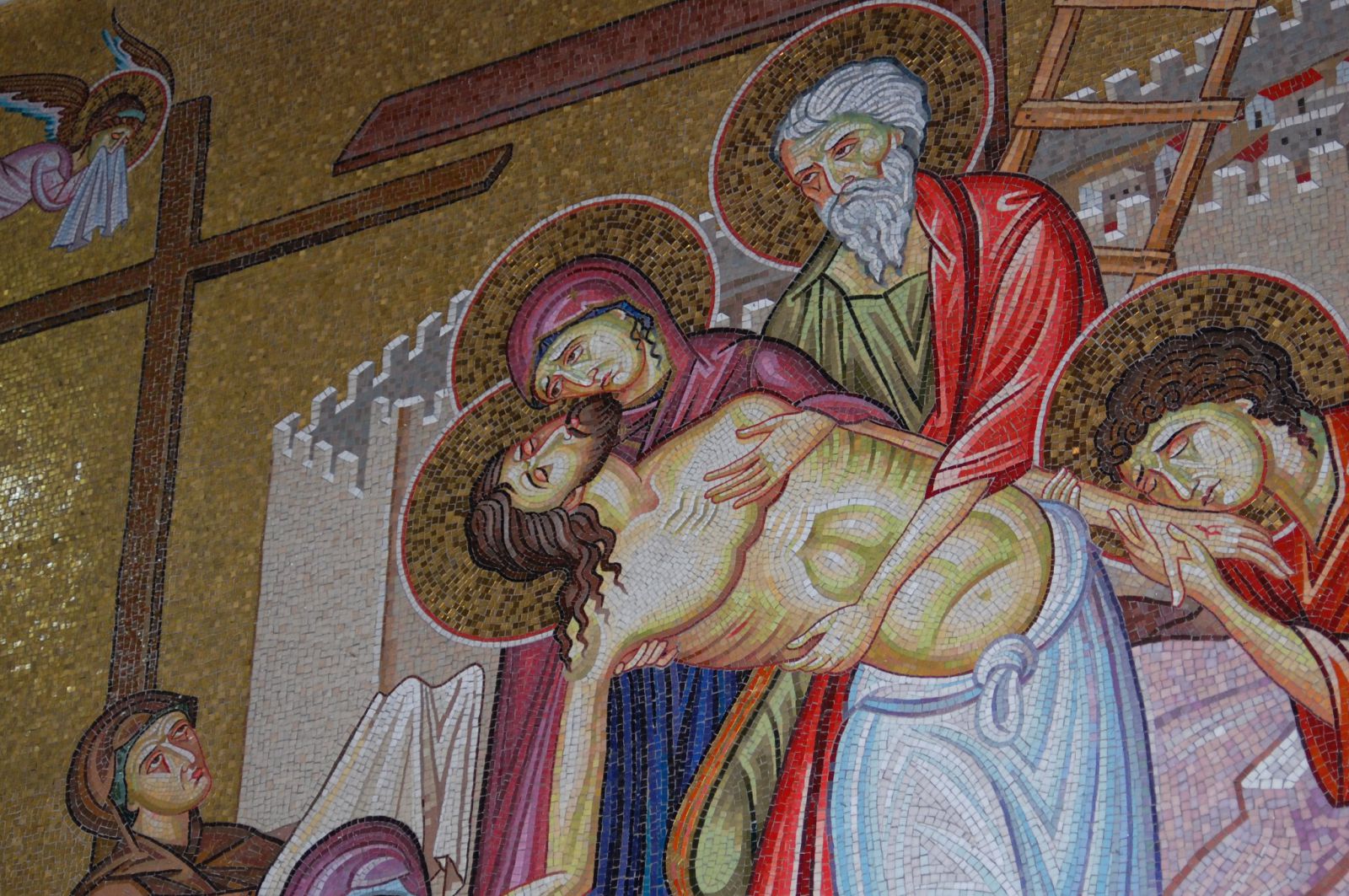

First, I was expecting to feel more in going to places where Jesus was. I was thinking that I'd experience some deep connection that I couldn't get elsewhere. I was wrong. I was wrong because those sites are now empty, built upon. Places like the Garden of Gethsemane, where you can see some olive trees that were standing there in Jesus' time – that's pretty cool. But it's got a fence around it, with a big Orthodox church there commemorating the whole thing. Sometimes it was low key and tasteful. Sometimes it was over-the-top religious kitchy. But it was always there: construction. Hate to sound like a lit. theory major, but I always felt that I was dealing with someone's construction of what my spiritual experience should feel like. It wasn't enough to stand in a field where Jesus preached his Sermon on the Mount; I had to be in a garden run by Franciscans with little plaques with Bible verses placed carefully between rose bushes. It was nice, serene, meditative. But it wasn't the place where Jesus had stood. That had been torn down and built over. There was now

some olive trees that were standing there in Jesus' time – that's pretty cool. But it's got a fence around it, with a big Orthodox church there commemorating the whole thing. Sometimes it was low key and tasteful. Sometimes it was over-the-top religious kitchy. But it was always there: construction. Hate to sound like a lit. theory major, but I always felt that I was dealing with someone's construction of what my spiritual experience should feel like. It wasn't enough to stand in a field where Jesus preached his Sermon on the Mount; I had to be in a garden run by Franciscans with little plaques with Bible verses placed carefully between rose bushes. It was nice, serene, meditative. But it wasn't the place where Jesus had stood. That had been torn down and built over. There was now an edifice guiding my experience, telling me how to feel and connect. That bugged me. I know there's been a lot of time for historical accretions, layers and layers of that sort of thing piling up over important spots. I just wished they hadn't. They got in the way. And I guess I can't fix that without a time machine.

an edifice guiding my experience, telling me how to feel and connect. That bugged me. I know there's been a lot of time for historical accretions, layers and layers of that sort of thing piling up over important spots. I just wished they hadn't. They got in the way. And I guess I can't fix that without a time machine.

The other thing that struck me was the absence of Jesus. Not that these were God-forsaken places, that the Spirit of Christ wasn't there, or anything like that. Just that Jesus physically wasn't there anymore. I wasn't going to run into him, see him in the flesh. That time was past (so again, anyone got a time machine). But more than that, I started feeling like it didn't really matter that he wasn't there in the flesh. It's not about this mountain or that mountain, but about Spirit and truth (Jo. 4:19-24). The guide we had at the Garden Tomb summed it up beautifully. There are actually s everal sites that claim to be the place where Jesus was buried, the most ostentatious of which is the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Garden Tomb is run by an English in

everal sites that claim to be the place where Jesus was buried, the most ostentatious of which is the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Garden Tomb is run by an English in ter-church group, and they make a pretty good case that theirs is the garden where Joseph of Arimathea had Jesus' body interred. Our guide was an unassuming older man, maybe in his early 60s, looked like a librarian with his wire-rimmed spectacles. He showed us where Jesus might have been crucified, and we read from John to get a sense of the place back then. He took us to the tomb. But then he said, "Jesus might have been crucified over there and buried here. But what really matters isn't the exact spot where these things took place. The thing that really matters is that he isn't there anymore. He's risen." And I thought, "Quite right. Thanks for bringing that home." In this case, the absence of Jesus is positively good news.

ter-church group, and they make a pretty good case that theirs is the garden where Joseph of Arimathea had Jesus' body interred. Our guide was an unassuming older man, maybe in his early 60s, looked like a librarian with his wire-rimmed spectacles. He showed us where Jesus might have been crucified, and we read from John to get a sense of the place back then. He took us to the tomb. But then he said, "Jesus might have been crucified over there and buried here. But what really matters isn't the exact spot where these things took place. The thing that really matters is that he isn't there anymore. He's risen." And I thought, "Quite right. Thanks for bringing that home." In this case, the absence of Jesus is positively good news.

The last thing that bugged me about our journeys within Israel was the sense of tension, of oppression, of alienation, even hatred. When the Israeli Jews won in 1967, they had a bunch of Palestinians in the territory they now occupied. They could have either deported them all (in effect, ethnically cleansed the land), but they didn't. Probably because the Arab countries around them wouldn't have taken them in, for fear of being overwhelmed. They could have treated them like equals and made them all citizens, with all the rights of citizens. But they didn't, partly out of fear that they'd be out-voted in the Knesset, partly because perhaps they didn't really feel they were equal to them. In an ethno-religiously oriented state like Israel, some are more equal than others (to quote Orwell). So they neither deported nor accepted. They remained, and remain, in this weird limbo which requires the use of a lot of guns, a lot of barbed wire, and a wall (an unjustly drawn wall that divides Palestinian communities).

The last thing that bugged me about our journeys within Israel was the sense of tension, of oppression, of alienation, even hatred. When the Israeli Jews won in 1967, they had a bunch of Palestinians in the territory they now occupied. They could have either deported them all (in effect, ethnically cleansed the land), but they didn't. Probably because the Arab countries around them wouldn't have taken them in, for fear of being overwhelmed. They could have treated them like equals and made them all citizens, with all the rights of citizens. But they didn't, partly out of fear that they'd be out-voted in the Knesset, partly because perhaps they didn't really feel they were equal to them. In an ethno-religiously oriented state like Israel, some are more equal than others (to quote Orwell). So they neither deported nor accepted. They remained, and remain, in this weird limbo which requires the use of a lot of guns, a lot of barbed wire, and a wall (an unjustly drawn wall that divides Palestinian communities).

The Israeli Jews want security, and who can blame them. There are a lot of Muslims in the area that want to kill every Jew. There are many Arab school rooms that have a blank space where the state of Israel is supposed to be. But the Israeli response has been to isolate and dehumanize the Arabs in their territory, some of whom are Arab Christians. Israel's strategy has done nothing but radicalize the Muslims in the area, and the Arab Christians often find themselves caught in the middle, and many have fled. That tension and mutual suspicion makes it hard to swallow the "blessed land of God's beloved" line that some Evangelical Christians espouse. Israel is a land of contradictions, a land in pain. And the only way healing will ever come is if both sides repent of their humiliating and hostile treatment of the other, and forgiveness of each other's past humiliating and hostile treatment of them. In other words, I just don't see a way out, short of a spiritual awakening of a Christian kind. Short of that, I'm not sure Israel will ever be at true peace.

Let me give you a brief vignette of the kind of contradictions and weirdness that Israel trades in. My 14-year-old daughter, Ruth, is our resident animal-lover. She demanded that we have a camel-riding experience. And not just a "gas station camel," either. In Southern Israel, Israeli Arabs often have camels parked right outside of gas-stations. You can pay 20 shekels for a 15 minute ride for your kid. But Ruth would not be satisfied with that - she wanted the real deal. So we found a place in the desert outside Jerusalem called "Genesis Land." Sounds cheesy, but it was a lot of fun. Eliezer, Abraham's servant, greets us. We ride as a group on camels (horrendously tall beasts) to Abraham's tent, where Abraham welcomes us and offers us hospitality (dates and raisins, no bread since it was Passover week). And then the group does some group activity. Our group herded sheep and goats.

Let me give you a brief vignette of the kind of contradictions and weirdness that Israel trades in. My 14-year-old daughter, Ruth, is our resident animal-lover. She demanded that we have a camel-riding experience. And not just a "gas station camel," either. In Southern Israel, Israeli Arabs often have camels parked right outside of gas-stations. You can pay 20 shekels for a 15 minute ride for your kid. But Ruth would not be satisfied with that - she wanted the real deal. So we found a place in the desert outside Jerusalem called "Genesis Land." Sounds cheesy, but it was a lot of fun. Eliezer, Abraham's servant, greets us. We ride as a group on camels (horrendously tall beasts) to Abraham's tent, where Abraham welcomes us and offers us hospitality (dates and raisins, no bread since it was Passover week). And then the group does some group activity. Our group herded sheep and goats.

Stew and I stayed in the tent to talk to Abraham (or the guy playing Abraham). He was interested in us since his friend was marrying a Czech girl, and he knew my family was from Prague. "Abraham" was actually a friendly Jewish guy who grew up in Grand Rapids named Josh. And he talked a lot, and was interesting to listen to. I was especially interested, since he and everyone who worked at Genesis Land lived in a settlement called Yisuv Alon. Settlements are considered illegal by the U.N., because they are built on disputed territory (land claimed by both Israeli Jews and Palestinians). The Israeli government gives generous subsidies to Jews who are willing to band together in groups and go out and start towns as a way of claiming the disputed land. It's a sure-fire way of undermining the peace process before it gets started.

My image of settlers had been religious, ultra-Orthodox hard-liners, angry, bitter people who had tons of kids and hated Palestinians (including Palestinian Christians). But this wasn't Josh. Josh was friendly, open, into making connections with people, said he didn't hate anyone, but just wanted to practice a lifestyle of hospitality. And he spoke of peace, even as he was actively participating in a community that was undermining peace. Israel is a land of weird contradictions, just like that.

It was hard to be a spiritual tourist while feeling that vibe, those contradictions, those tensions. It was hard to get in touch with the land as it was when the present was just so darned insistent, like an annoying 3-year-old constantly trying to get your attention. I enjoyed the times when my family and I were chilling on the beach, or when I got to read aloud to them in a restaurant (Ursula LeGuin is absorbing reading anywhere on the globe). It made me forget the pain and hypersensitivity that Israel seems wrapped up in, even as it pursues an ever more commercial lifestyle (probably as a strategy for trying to forget the pain too).

So, I don't know exactly what I was expecting, but it wasn't that. If you ask me how Israel was, I'll tell you, "Beautiful and weird." Full of sunshine and contradictions and pain.

P.S.: I ought to add that my wife found the trip really helpful in grounding her sense of historical place for the Bible stories she teaches, as well as getting a feel that "yeah, this happened in time and space, here." And I felt that some as well. It's true - being there gives you a feel for the land and its history. Also my eldest daughter said that for her, it was deeply moving on a spiritual level. So I can't say that my experiences are representative even of my own family. Still, the present situation of Israel is a reality like a raw wound, and I don't think spiritualizing our experiences erases or heals that.

Recent comments

7 years 47 weeks ago

9 years 7 weeks ago

9 years 24 weeks ago

9 years 24 weeks ago

9 years 28 weeks ago

9 years 36 weeks ago

9 years 37 weeks ago

10 years 12 weeks ago

10 years 25 weeks ago

11 years 2 weeks ago