Further Thoughts on Ra's Al Ghul: Totalitarian "Justice," Natural Selection, Batman, Compassion, and Human Rights

[As if you needed warning: SPOILERS AHEAD!]

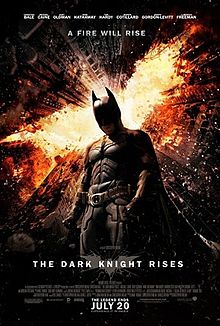

(Images courtesy of and copyrighted by DC Comics and Warner Bros. Pictures).

After I posted my blog post "Maintaining the Balance" last week, a friend and ex-student Tweeted at me that I'd gotten the motivation of the League of Shadows (Ra's' ninja organization) wrong. I had argued that Ra's' main motivation (and that of his daughter and Bane) had been to destroy Gotham in some Daoist, Eastern mystical attempt to "restore the balance." Since this friend of mine is an incredibly bright guy, I thought that I ought to go back and rewatch Batman Begins, since it had been years. It turns out that my friend was partially correct. Here's what I mean:

I was partially right about the Eastern mystical concern for balance. But what I had overlooked was The League of Shadows' commitment to what they called "justice." As far as I could figure out, "justice" is an abstract ideal that the League uses to determine when a society or city has become too corrupt and past salvation. They would then destroy that city to "restore the balance" and allow justice to flourish. So, Ra's tells Bruce Wayne, the League had initiated the Black Plague and other disasters to weed out humanity's corrpution, much like pruning a vine to create a healthier plant. Bruce finds that he cannot follow his mentor's path when confronted with a convicted murderer whom he is to execute. Wayne's response: "I'm no executioner."

If you listen to Ra's thinking on a worldview level, you'll find a curious mixture of various totalitarian ideologies (Marxism and fascism come to mind) and atheistic Darwinism (the survival of the just, in this case). Of course, it's not real Darwinism, for in Darwinism, the mechanism is an impersonal natural selection. With the League, it's a group making the species more fit for survival. But the rhetoric is similar: the weak (or unjust) must perish for the survival of the whole species. And the missing ingredient in both Darwinism and in Marxist or fascist totalitarianism is individual human rights, the idea that each individual has dignity and is worth protecting, regardless of objective worth. That's what Bruce Wayne brings to the table. That's why Batman must fight Ra's Al Ghul in Batman Begins, the Joker (not so much totalitarian as anarchist) in The Dark Knight, and Al Ghul's daughter and henchman in Dark Knight Rises. It's his compassion for the individual, worthy or unworthy, that sets Batman apart from the villains. That compassion is a cultural inheritance from the West's Jewish and Christian past.

Or so argues Lutheran political scholar Glenn Tinder. In 1989 (an important year for human rights, especially for those of us living in Central and Eastern Europe), Tinder wrote an article for The Atlantic Monthly called "Can We Be Good without God?" I make it required reading for students in my Comparative Worldviews class, because it's brilliant and full of insights about the political implications of Christianity, or the rejection of Christianity (the kind of militant secularism embraced by the New Atheism). In it, he argues that what we hold most dear in our political systems in the West, the cherishing of individual human rights, is the direct result of Christian ideals such as agape (mercy to the undeserving), the image of God (everyone has dignity as a human being), and sin (everyone is tainted by the distorting power of sin, and so care must be taken when dealing with each other - abuse is all too easy, all too human). It is only in recognizing the authority of the God-man that these things can be kept in balance. Eject him from our political thinking, and we replace the God-man with what he calls the "man-god," groups of humans who take on themselves divine privileges to judge people according to their own agendas and visions of "justice."

Ra's derisively calls Bruce Wayne's belief that even criminals need protection "idealism." Ironically, according to Tinder, it is not the Bruce Waynes of the world, but the Ra's Al Ghuls and the Banes, who are the real idealist, projecting abstract notions of justice that crush individuals underfoot. Wayne is grounded, restrained, by his respect for the Christian roots of Western civilization. Even though he has no use for Christianity per se, Bruce Wayne follows it's line of thinking, and even apples it to himself and his relationship with his butler, Alfred. The consoling refrain from Batman Begins is Wayne's tiredly pleading question to Alfred, "You haven't given up on me yet?" and Alfred's terse and faithful response, "Never." (And that gives emotional depth to Alfred's final abandonment of Bruce Wayne in The Dark Knight Rises, because Alfred cannot stand to be force to watch Wayne's self-destructive path reach its conclusion). So even though Batman is very much about a self-saving humanity ("We can save Gotham," he tells Commissioner Gordon), his mission and passion resonate with themes that make sense finally ultimately only in a gospel-context where the worthy sacrifices himself for the unworthy, where even heros fall and need others not to give up on them, where everyone (including criminals) need and receive mercy, abstract concerns for "justice" and "balance" notwithstanding. Though Ra's calls Wayne's compassion "a weakness," it is the only thing that marks him as a true hero, a hero worth lauding and even emulating.

So I'll stand by what I originally said: Hollywood draws upon Chrstian notions without knowing where they come from, without honoring the one who gave them. Without the gospel, heroism as we know it in the West, as we've come to love in Batman, would be nonsense. I'm hoping and praying for someone as talented as Christopher Nolan or Alan Moore, but who knows God, could produce a hero mythos as unsentimental and powerful as Batman, but connected to its roots, connected to the source of the fount of mercy and compassion.

Comments

Another worldview analysis of the recent Batman movie